I learned the concept of linearizability and sequential consistency this semester in CS425 (Distributed System). To implement these two kinds of consistency models, we could consider the algorithms that use total order broadcast. At first, I was really confused about the philosophy behind the scene: why total order broadcast is necessary for write request in both models? And why total order broadcast is only necessary for read request in linearizability but not sequential consistency? I will try illustrating the idea in this article with some toy examples.

1. Implementation with total order broadcast

First, let’s have a quick review of the implementation of both models.

Linearizaiblity

- When read request arrives: broadcast the request. When own broadcast message arrives, return value in local replica.

- When write request arrives: broadcast the request. Upon receipt, each process updates its replica’s value. When own broadcast message arrives, respond with ack.

Sequential Consistency

- When read request arrives: immediately return the value in local replica.

- When write request arrives: broadcast the request. Upon receipt, each process updates its replica’s value. When own broadcast message arrives, respond with ack.

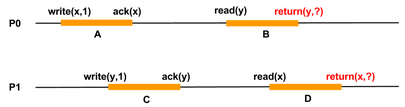

Suppose there are two processes P0 and P1. Both processes maintain the replica of two shared variables x and y. The initial values are both 0. The black lines in all figures represent the real time line.

2. How should linearizability look like?

First let’s consider the “linearizability”. What should request B and D return in order to achieve the “linearizability”? According to the definition, we should have the following constraints (Notice: here each operation is supposed to be instantaneous, which means that each ack/return happens right after receiving write/read request):

Ahappens beforeBChappens beforeDAhappens beforeD(withDreturns 1 implicitly)Chappens beforeB(withBreturns 1 implicitly)

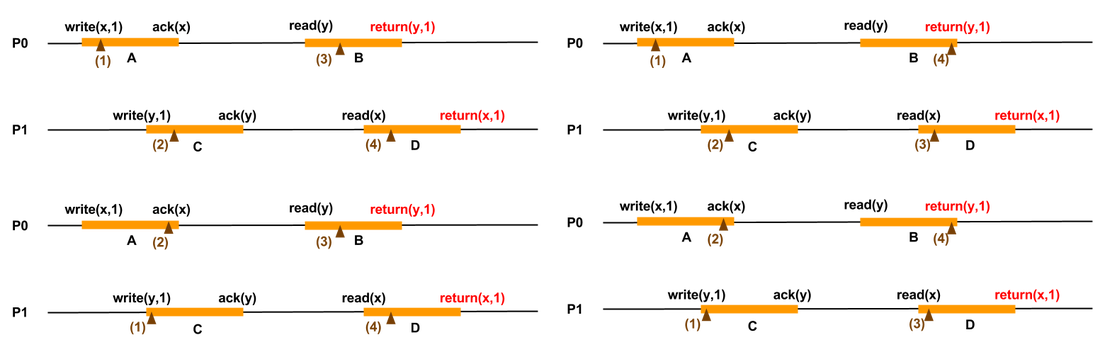

To satisfy these order constrains, four permutations of these operations could be derived:

3. How should sequential consistency look like?

So far (hopefully) you should be pretty clear about how the permutations that satisfy the “linearizability” are derived. Let’s move on to “sequential consistency”. “Sequential consistency” is a weaker condition than “linearizability”. By “weaker”, I mean “sequential consistency” does not force the permutation to respect the real-time order of non-overlapping operations as “linearizability” does. Instead, respecting the real-time order within each process is enough. Thus we could get rid of the last two constraints of “linearizability” for “sequential consistency”:

Ahappens beforeBChappens beforeD

In this case, besides the four permutations (Figure 2) satisfying the “linearizability”, two more permutations that only satisfy “sequential consistency” but not “linearizability” could be derived:

Let’s do some wrap up. So far, we derive four permutations (with the corresponding return values of read requests) for “linearizability”. These four permutations also satisfy “sequential consistency”. Besides these, we also derive two permutations that only satisfy “sequential consistency”. In total, 4 for “linearizability” and 6 for “sequential consistency”.

4. Write request

As we know, to implement “sequential consistency”, total order broadcast of the write request is needed.

Why broadcast the write request?

This is pretty straightforward and trivial. The write request should be broadcasted since we want to maintain the consistency among all replicas in a distributed systems. For example, suppose you add an item to your shopping cart on Amazon and this “write” operation is conducted by one of the replicas. If you check your shopping cart later at another place and this “read” operation might be conducted by another replica. Under this scenario, what you expect to see is a shopping cart with the item you added previously, instead of an empty one.

Why total order broadcast the write request (for sequential consistency)?

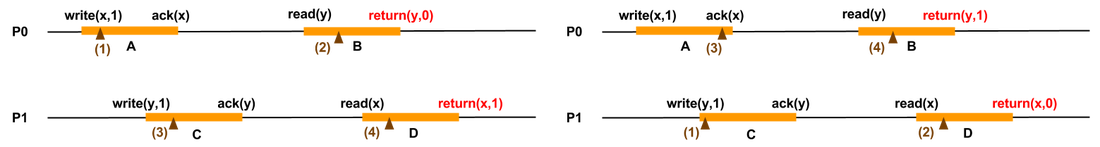

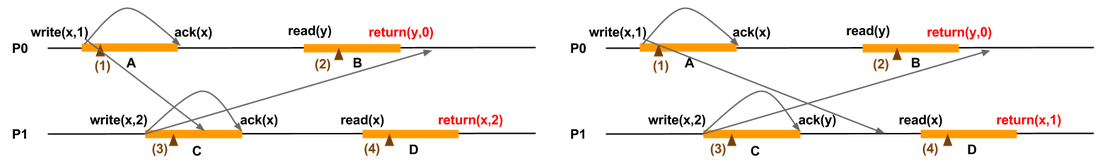

So far, we know we should broadcast the write request. But why the broadcasts should be in total order in order to achieve sequential consistency? Let’s first take the left case in Figure 3 as an example.

In the left case of Figure 4, request A arrives before request C at both P0 and P1. In the right case, however, request A arrives before request C in P0 while the order is reversed in P1. Sequential consistency are satisfied in both cases no matter whether the write request broadcasts are in total order or not. Hmm, can we just come up with the conclusion that the broadcasts are not necessarily to be totally ordered?

Nope! Let’s try another example by making a trivial modification: change operation C from write(y,1) to write(x,2). Now let’s see what happens.

I suppose you have noticed the difference :D The sequential consistency condition with A->B->C->D order implicitly indicates B returns 0 and D returns 2. This works perfectly good with the left case where total ordered broadcast is used. But in the right case where broadcasted write requests are not in total order, x returns 1 instead of 2. The right case does not maintain sequential consistency.

Intuitively, the takeaway here is if multiple processes try to modify the same variable, we need to guarantee that these modifications happen in the same order among all replicas. Otherwise, conflict will arise (like right case in Figure 5).

5. Read Request

To achieve “linerizability”, we also need to total order broadcast the read request besides write request.

Why also total order broadcast the read request (for linearizability)?

This is a good question. You may wonder why it is necessary to broadcast the read request since it will not actually cause any change to any replica.

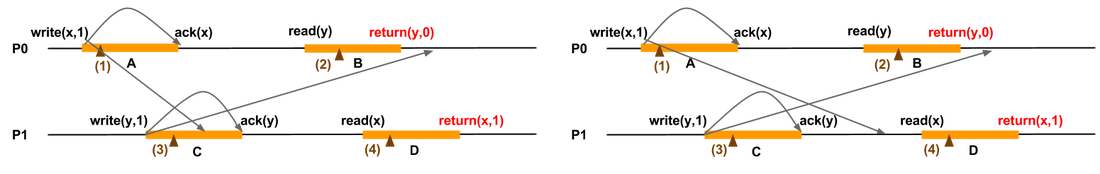

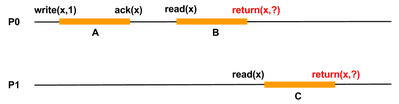

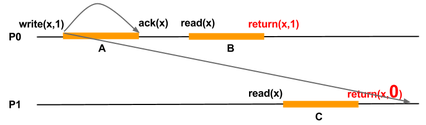

For this part, we will use the example in Figure 6 as illustration.

Now let’s do a simple quiz. What should B and C return respectively in order to maintain “linearizability”? Think about it for five seconds and then compare your solution with Figure 7.

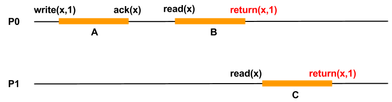

Hope you get the correct answer! To put it short, “linearizability” requires the three operations to happen in A->B->C order. Thus B and C must show that they have seen the effect of A. Then the question comes again: what do the request broadcasts look like behind the scene? Let’s first only consider the total order broadcast for write request since we have discussed it previously.

The scenario in Figure 8 seems good: linearizability is maintained only with broadcast of write request. But never forget that it is just one of the possibilities. We cannot guarantee that the broadcast message always arrive at a perfect time. Believe it or not, let’s have a look at the scenario in Figure 9.

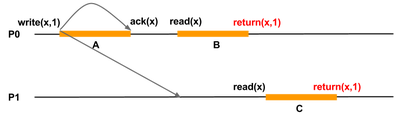

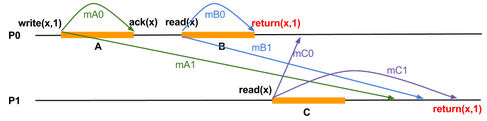

Oops, that is not what we expect. As discussed before, we require C to return 1 to maintain “linearizability”. But since P1 sees the effect of A (receives A’s broadcast message) after receiving its own read request C, it could only return 0 instead of 1. “Linearizability” cannot be reached. Then comes the question again: can we figure out an approach that helps “linearizability” survive both cases (Figure 8 and Figure 9)? That’s the reason why we need total order broadcast of read request, as is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 may seem a little bit messy at the first glance, thus I differentiate the broadcast messages of requests with different colors and message ids. For example, the “green” messages mA0 and mA1 are the broadcast messages of request A to P0 and P1 respectively.

From the figure we can see the total order broadcast is used to guarantee that requests arrive at P0 and P1 both in A->B->C order. How to implement the total order broadcast is beyond the scope of this article, thus for now you could just assume that there is some magic that guarantees such an order. We find that even though P1 still receives A after receiving C as in Figure 9, it delays the response of C until it could actually “see” the effect of A. In this case, P1 could return 1 for request C - the linearizability is satisfied!

Can you figure out why total order broadcast of read request is not necessary for sequential consistency as an exercise?